Teaching All Minds

Neurodiversity refers to all minds, whereas neurodivergent means having a brain that diverges from the dominant group. People who are neurodivergent may process information differently, explained Amy Hanreddy ’99 (Special Education), M.A. ’02, chair of the Eisner College’s Department of Special Education and co-director of CSUN Explorers, a program for students with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

For example, ASD is characterized by differences in social interaction, communication and sensory processing, while ADHD affects attention, impulse control and hyperactivity. Dyslexia affects reading and writing, while dyspraxia affects motor skills and coordination, and dyscalculia affects mathematical abilities. There are also people who identify as neurodivergent who do not have a specific diagnosis, Hanreddy added.

For those who want to study neurodivergence, CSUN offers highly regarded programs in psychology, general and special education, and an 18-unit minor in Disability Studies — the first of its kind in the California State University system. Graduates of these programs go into a wide range of fields, including working at inclusive local schools run in part by CSUN. And for neurodivergent students who do not qualify for traditional university enrollment, CSUN Explorers offers the opportunity to experience courses and college life.

CSUN’s dedication to neurodivergent students and those with other disabilities is “about dismantling systems that serve to segregate students who are perceived as different,” Hanreddy said. Future educators trained at CSUN, she said, “demonstrate exemplary practice in inclusive education.”

CHIME Model Leads the Way

The CHIME Institute — which celebrates its 35th year this year — is a groundbreaking partnership between CSUN’s Eisner College and the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD). The program’s highly successful model attracts educators and visitors from around the globe, from as far away as Japan.

The institute is made up of the CHIME Infant and Toddler Program for children identified for early support, the CHIME Preschool Inclusion Program and a transitional kindergarten (TK)-8th grade charter school in Woodland Hills called CHIME Institute’s Schwarzenegger Community School, which currently serves approximately 635 students. Additionally, it offers a teacher residency program in conjunction with the Eisner College.

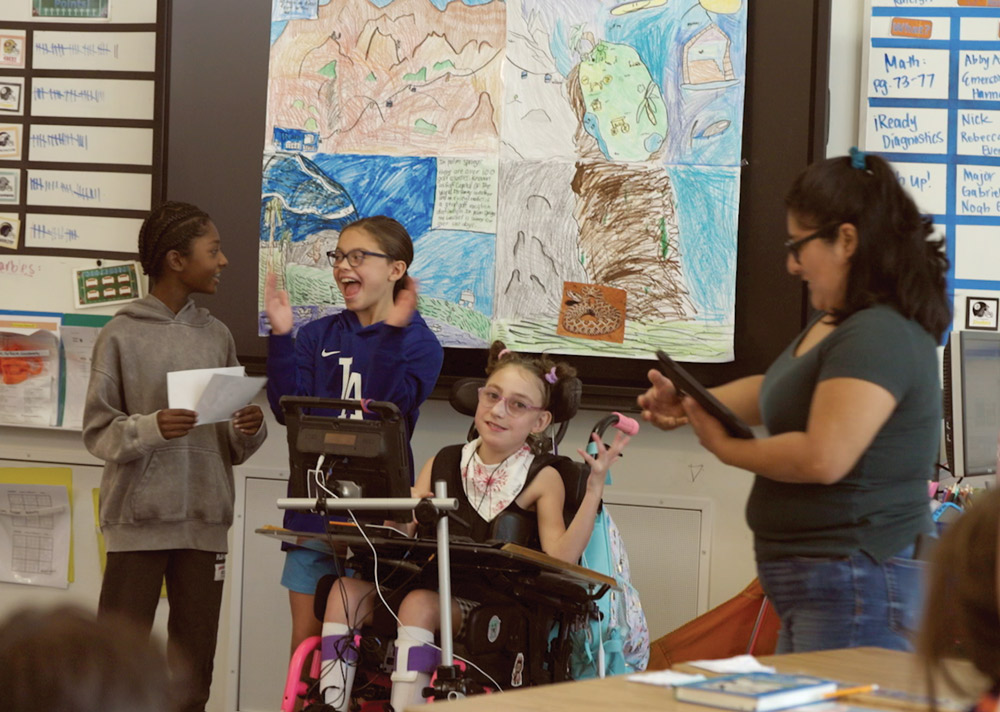

“We [are] creating classrooms in which all learners have the opportunity to authentically participate — and authentically learn and have agency and a place to belong in the classroom.”

A Place to Belong

Inclusive education helps children with ASD and other forms of neurodivergence achieve their maximum potential, Studer said. Meanwhile, student teaching and residencies at CHIME’s Preschool Inclusion Program and charter school help train the next generation of teachers to work with all learning abilities — from children who need high levels of support in the classroom to those who are gifted.

While schools nationwide are trending toward inclusive education practices like CHIME’s, Studer said schools that do not follow its model split up their most precious resource: “the highly educated adults who come to work there.” Non-inclusive schools run essentially segregated, separate-track programs for students who are typically developing, those who are gifted, those who have disabilities and those who are English-language learners.

At CHIME, “we do the opposite,” he said.

Collaboration in the Classroom

CSUN Eisner College faculty helped establish the CHIME Institute as a private nonprofit corporation in 1990. Its Preschool Inclusion Program launched first, soon followed by the CHIME Infant and Toddler Program. Both programs are still housed at CSUN, in collaboration with the Child and Family Studies Center, and they serve as demonstration and educator development sites for CSUN students.

The success of the early childhood program, coupled with the needs of the community, prompted a group of parents and CSUN faculty to develop a charter elementary school in 2001 and a charter middle school in 2003. The elementary and middle schools merged in 2010 and were named the Schwarzenegger Community School, which now serves TK through 8th.

For CHIME students who are gifted or need little classroom support, there are still benefits to inclusive education, including increased empathy, Studer said.

“There’s something inherent in the model where students with disabilities are learning side by side, in high-quality, standards-based instruction, with their typically developing peers,” he said. “It works and we can show it, not just in the fact that kids are included, or that they have a wide range of friends, or that they’re learning social skills and empathy, but they are getting solid academic achievement out of this model as well.”

As they celebrate this 35th anniversary year, Studer and CSUN leaders marvel at the full-circle moments, such as current CHIME teachers who got their start as preschoolers in CSUN’s Lab School — which partners with CHIME on its Preschool Inclusion Program — and CHIME graduates who go on to CSUN to earn bachelor’s and graduate degrees, or to attend the CSUN Explorers program.

CHIME also hires Eisner College graduates, many of whom spend time as student teachers or residents at the charter school.

Honoring the ‘Variation of Human Minds’

At CSUN, those supports may look different for each neurodivergent person, said Ellen Stohl, a professor of Disability Studies and co-director of CSUN Explorers. One student may wear headphones because they need to mute loud sounds. Another may need to stand or take frequent breaks from the classroom. Others may need lectures recorded and transcripts provided to help with processing spoken information.

Stohl, who advises the student club DISRUPT (Disabled Individuals Rising Up for Systemic Transformation), noted that several CSUN faculty and staff also identify as neurodivergent, increasing representation on campus. Communication studies lecturer Kelly Opdycke has written about her experience as a neurodivergent faculty member, and assistant professor of philosophy Johnathan Flowers speaks and writes about his experiences with neurodivergence, specifically ADHD.

Supporting Diverse Learners

“This takes willingness to support diverse learners,” she said. Future classrooms might have modular spaces where students can stand, sit or even lay down if needed. Students might be invited to present information mastery in a variety of ways — not just on tests, but in small-group presentations, journals, drawings and art projects, or via mobile device.

Because neurodivergence can be invisible, Stohl said, the onus is often on students themselves to communicate their needs to professors, peers and others on campus — in order to get accommodations and support. She challenged professors to invite those conversations by including a disability-related statement on each course syllabus.

“We have to communicate with our students about it, but for people for whom communication might not be their greatest skill or ability, how do they tell me what they need?” Stohl said. “In my classrooms, students can email, they can journal, they don’t have to come talk to me in person. I’m never going to judge.”

Neurodivergence is not the same as disability, and not all who identify as neurodivergent need additional supports when it comes to classroom learning, Hanreddy said. However, neurodivergent students who are interested in support services have a wealth of resources available at CSUN, at the Disability Resources and Educational Services (DRES) office. Students can register with DRES, located in Bayramian Hall 110, or call (818) 677-2684 or email dres@csun.edu.

From Explorers to Employees

“CSUN Explorers can fully access a college experience and work toward their employment goals,” Hanreddy said.

Professor emerita of special education Beth Lasky ’73 (Psychology), M.A. ’77 (Special Education) created the program to break down stereotypes and encourage participants to engage in university life, while also building skills to expand their employment opportunities. Among the first cohort was a young woman who had attended the CHIME Institute Preschool Inclusion Program.

“Everyone in that first cohort — including some who were on the spectrum — passed their classes,” Lasky said. “Some of them got accommodations from the faculty member, [and] others did not need them.”

Participants are required to take up to two classes per semester and participate fully, and they often exceed their own expectations, according to Lasky and current Explorers co-directors Hanreddy and Stohl.

Faculty shared how much they appreciated having Explorers in their classes, because they set a positive example for neurotypical students and often came to class better prepared, Lasky said.

Explorers do not earn a CSUN diploma, rather they are awarded a certificate for participation and working toward their employment goals. The second year of the program includes an internship opportunity on campus or in the community.

Community Support at CSUN

At the university’s Autism Research Laboratory and Autism Clinic, run by the Department of Psychology in the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences, therapists assess, design and implement individualized behavioral interventions for individuals with ASD. The lab also conducts research on specific intervention techniques, based on the science of Applied Behavior Analysis.

Professor emeritus Ron Borczon, who started the program in 1984, said he’s encouraged by the recognition music therapy has received from other segments of the scientific community. “There’s a lot of collaboration between neuroscientists and music therapists, to see how the brain is affected by music,” Borczon said.

And in the Eisner College, the Family Focus Resource Center helps families raising children with disabilities, through education, advocacy and family support services.

“We’re very connected to the community,” Hanreddy said.

Whether students come to CHIME’s Infant and Toddler Program because they are identified for Early Start services, or to the Eisner College Special Education Literacy or Educational Therapy clinics for help, there are numerous entry points for local children with neurodivergence to benefit from support and resources, she said.

Early Assessment and Identification are Key

“When students are identified early in their lives as having an impairment or a disability — and their parents and families learn how to utilize the supports available to help them be successful — those students are prepared with the knowledge they need to be successful, along with receiving the outside supports they need,” Stohl said.

But when students with neurodivergence are identified later, or perhaps never formally assessed, they may miss opportunities for accommodations and building confidence.

“If we just taught through special education in diverse ways and respected that everybody’s neuro processing is different, we would not have to diagnose to get the supports,” Stohl said. “The supports would be built into the system. But because we look at disability as a deficit, you have to get a label to get the supports you need to be successful.”

“If we just taught through special education in diverse ways and respected that everybody’s neuro processing is different, we would not have to diagnose to get the supports. The supports would be built into the system. But because we look at disability as a deficit, you have to get a label to get the supports you need to be successful.”

“That class is focused on inclusive education and accessibility, which encapsulates the heart of our department — we focus on promoting full access to the curriculum, and full access to school communities for all students with disabilities,” Hanreddy said.

Lasky, who helped develop the Disability Studies minor, said educators trained at CSUN in inclusion help spread opportunity in classrooms at CHIME and across the nation.

Stohl, who started her career as an inclusion aide at the Lab School and later worked as an inclusion staff member at the CHIME Preschool, said inclusion for students who are neurodivergent or have disabilities should start at TK, to provide the best chance for future success.

“It’s about changing the system and the way we see impairments, and realizing that everyone experiences disability and everyone is diverse,” she said. “Now, with technology, we can help find supports and make things easier for people, like a communication device that will speak for you. We used to think people who were nonverbal were non-thinking.”

Prepared for Educational Leadership

“We help students understand what neurodiversity really means for them as a learner, and then we select strategies and approaches that make them the most effective learner and worker they can be,” Studer said. “What neurodiversity cannot be is a reason why we opt out of teaching and learning.”

Studer credited his CSUN graduate education with preparing him to lead at the CHIME Institute and serve a diverse community, including neurodivergent students.

“The doctoral program (in Educational Leadership and Policy Studies) helped me understand how to recognize systems of education and how to change or improve those systems,” he said. “It also helped me be a good reader of research and interpret what the research is saying about educational practice, and how that can bridge to classroom practice.”